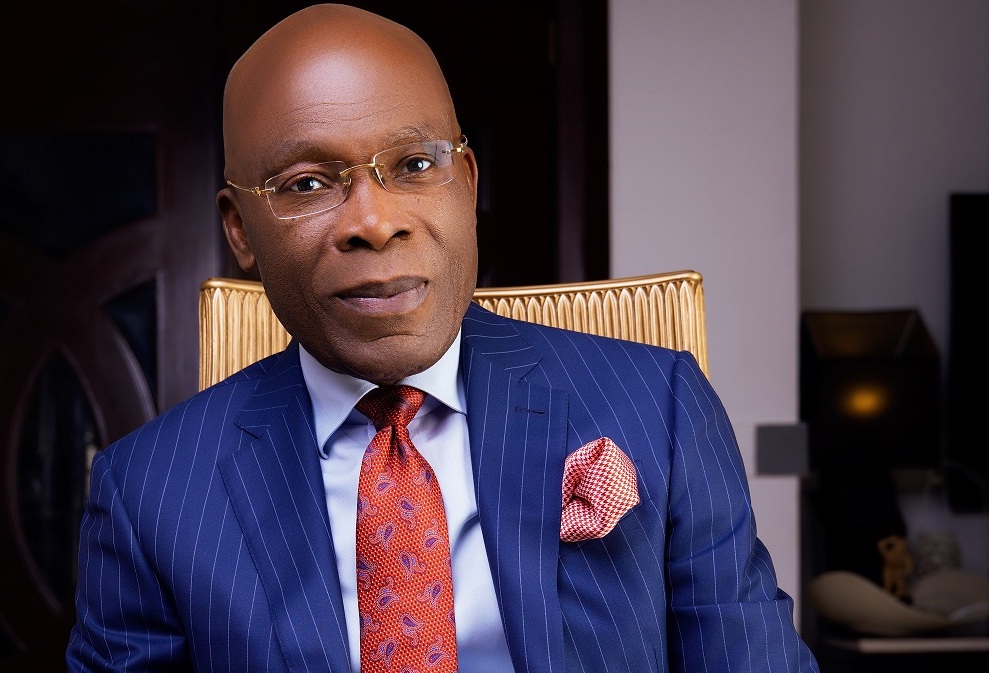

Economist, Daramola Omoyele has advised the government to include religious institutions in the new tax net in Nigeria, emphasizing that the new tax reform, though well-intentioned, would fail if it exempts the most powerful while burdening the powerless.

In an interview with the News Agency of Nigeria on Wednesday, Omoyele acknowledged that the new Nigeria Tax Administration Act (2025) introduced a unified tax identification system, stricter compliance measures, and new levies intended to expand the tax base.

He noted the existing protections for the less privileged, stating that “The government also raised the personal tax exemption threshold to ₦800,000 annually, a move meant to protect the poorest Nigerians.”

However, he cautioned that “Yet in practice, many will still face multiple local levies, consumption taxes, and other indirect charges that drive up the cost of living.”

Omoyele stressed that the critical but often ignored aspect of the reform was the exclusion of religious institutions from the tax net.

He observed that in today’s Nigeria, “it is almost impossible to separate many pastors or imams from their ministries,” pointing out that religious leaders were often wealthier than the institutions they led, owning fleets of luxury cars, private jets, and mansions while their congregations struggled to survive.

He said while some of the religious leaders were also corrupt, some equally manipulate their followers using faith as a shield to enrich themselves without scrutiny or accountability.

Omoyele pointed out the conflict between religious giving and civic duty, noting: “Many Nigerians are far more willing to pay tithes, offerings, or “seed sowing” than to pay taxes. Through these religious payments, some leaders have built vast personal empires, while ordinary citizens bear the cost of public services. This is not simply a spiritual issue, it is an economic one.”

He argued that tax exemption for religious leaders undermined public trust, as citizens see wealthy religious figures escape obligations that struggling traders must meet, adding that it also significantly weakens government revenue, as enormous sums flow untaxed through institutions that operate as financial powerhouses.

The economist asserted that there were strong moral and civic arguments for taxing religious leaders and institutions, which would hold leaders accountable for lavish lifestyles and massive untaxed income, uphold civic responsibility, protect the poor, and restore public trust.

He elaborated on the scale of untaxed wealth, stating: “Many religious organisations collect millions of naira daily in offerings and donations that go unrecorded and untaxed, even though they often exceed the turnover of many small businesses. When religious leaders live far above the economic reality of their followers, flying private jets and acquiring estates, fairness demands that they contribute back to the nation that sustains them. Preaching justice and fairness must go hand in hand with civic responsibility. Paying tax is not a sin; it is an act of service to society.”

Omoyele added that a fair tax system that includes all income sources would reduce the financial exploitation of followers, many of whom were pressured to give beyond their means.

The economist, however, strongly advised the government to also address corruption in the tax administration in the country.

He insisted: “until corruption is tackled and all income including religious wealth is fairly taxed, Nigerians will continue to view taxation as oppression, not obligation.”

He noted that the major obstacle to effective taxation in Nigeria was not merely poverty, but corruption, as many citizens were simply not convinced that the money they pay in taxes would ever be used for the public good.

He stated that the lack of transparency breeds distrust: “When tax revenue is mismanaged, stolen, or spent without transparency, people lose confidence in the system. It becomes difficult to convince market women and civil servants to pay taxes when they see public officials living extravagantly, roads collapsing, hospitals in ruins, and basic services failing,” a situation that leads many citizens to ask, “why should I pay when nothing changes?”

Omoyele concluded that as long as corruption remains unchecked, compliance in the tax system would remain low, regardless of the law.

He maintained that Nigeria’s tax system must be rooted in equity, transparency, and accountability, stressing: “Religious institutions should not be treated as sacred exceptions to civic duty. If big corporations like Dangote Cement or Seplat are required to pay taxes, then churches, mosques, and traditional temples that accumulate massive wealth should not be exempt. However, fairness also demands that the poor be protected. Over-taxing low-income citizens without addressing corruption or closing elite loopholes will only worsen inequality.”

He added that coupling enforcement with integrity, and showing Nigerians where their money goes, is essential, or the reform would remain “another beautiful policy on paper while poverty deepens on the streets.”